Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Full description not available

Z**B

A Brilliant History Lesson

Operation Mincemeat by Ben Macintyre (Harmony Books, New York: 2010) is an interesting story told brilliantly. Indeed, this is a great book and the way history should be written. it is well researched--Macintyre spent three years reviewing documents and conducting interviews but the writing is anything but dry, Macintyre tells the tale with relish. It works on several levels.While focused on but one intelligence operation during World War II--a misdirection of invasion plans served up to the Nazi war machine, the book really captures the essence of war time espionage and intelligence activity more generally because MaCintyre follows all the leads and provides insights beyond the mere operation that is the subject of his book.This is must reading for the intelligence practitoner --and the policymaker alike. One of the obvious lessons is the potential for intelligence collectors, analysts, and policymakers to be had. I am not giving anything away by providing the gist of the plot which was the subject of a much earlier book and film (both treated in the Mincemeat)--a dead body with bogus letters discussing a military invasion (away from the actual landing in Sicily) is positioned in the sea so as to fall into German hands. In intelligence parlance the acquisition of the letters by the German Defense Intelligence Service amounted to "documentary material," rather than quoting a living HUMINT source. And accordingly, the analytical mechanism focused on the documents rather than conducting a full analysis of the provenance of the materials. Now the letters were not crafted in a vacuum--the British knew well the potential for self-deception within the Nazi war machine because independent thought that might question the Nazi leaders perceptions was a risky business. Indeed, while reading this it was eerily familiar: in the run-up to the Iraq war there was a similar potential for self-deception within the analytical and policymaking apparatus--the President's advisors and the President himself were determined to remove Saddam Hussein through military action, intelligence that was not corroborated was seized upon as the rationale for the invasion. The inclination to be supportive of the policy goals, to be team players, was counter to the equal need to be skeptical of uncorroborated information upon which important decisions will be made. In the intelligence collection activity, there is a constant tension among all involved in the process in terms evaluating the bone fides of the intelligence acquired while still being supportive to all involved in the mission--and while being responsive to policy needs. The tension is necessary and helpful to the process and it can save lives and embarrassment--the opposite is true when the process is corrupted.Another key factor jumped out to me in the reading of this fine book. You could have the most ingenious intelligence plan in the world but it boils down to execution by people--and while there were certainly a cast of characters involved in Operation Mincemeat--the success of the mission was the result of the performance of just a handful of people, quality people.All of the key factors of the intelligence craft are on display in Operation Mincemeat: the personal antagonisms, petty arguments and disagreements within bureaucracies (even the wonderfully small ones that the British had then and still do) , the unpredictability of human behavior, the long hours of work, the requirement for secrecy as well as the need for the occasional "white lie" to protect sources and methods, the potential for self-delusion as I have indicated earlier, as well as the potential to achieve significant goals on the cheap.

L**Y

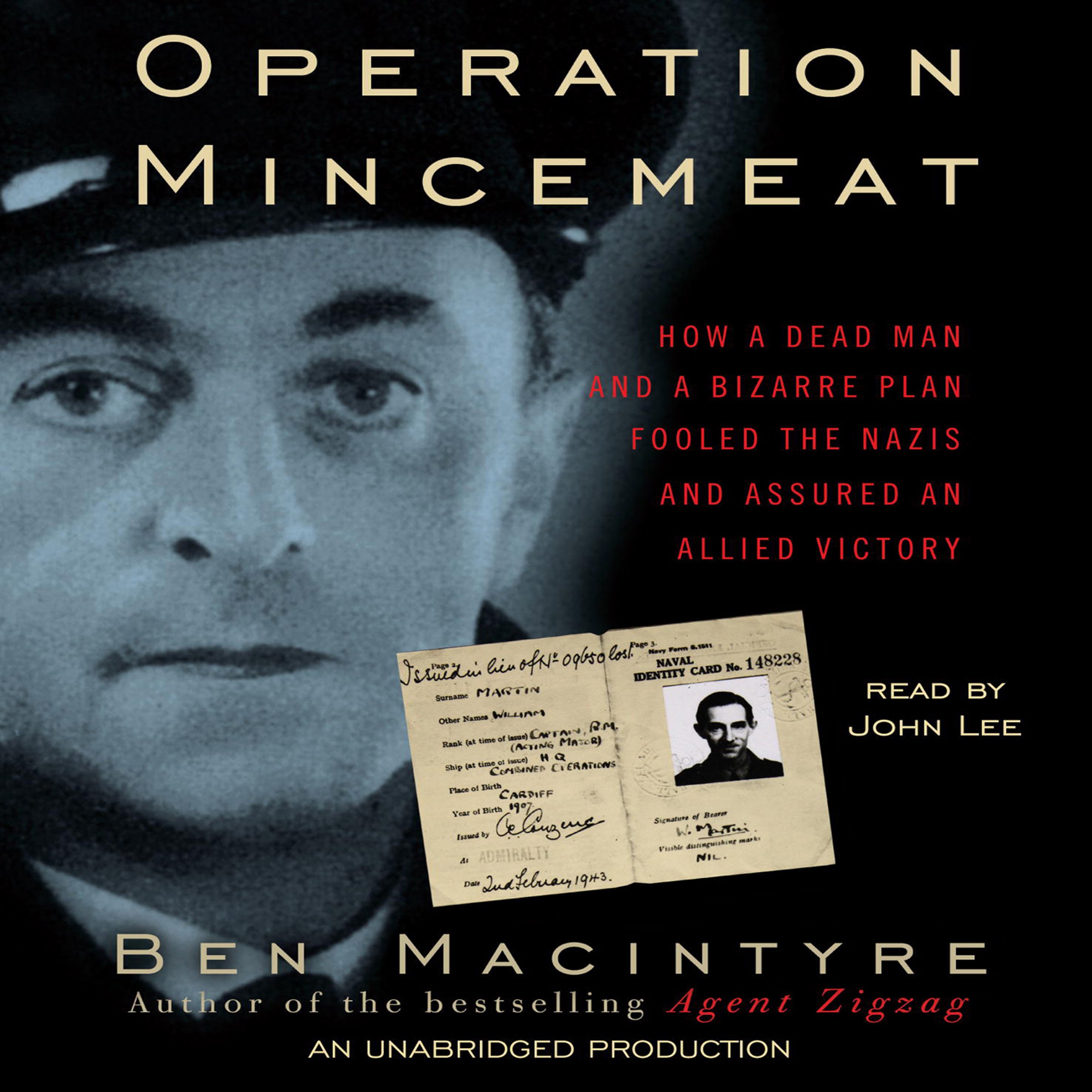

Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory

As a former FBI counterintelligence agent, I rarely read spy novels or books about spies. Authors rarely take the time to be accurate, so concerned are they that it fit the "action-packed" stereotype we've come to expect from books about spies. However, I was intrigued by the unique story of Operation Mincemeat and took a chance. I'd never read the other books written by Ben Macintyre so I wasn't sure what to expect. I'm a hard critic of spy books but I loved this one.For one thing, Macintyre captures the reality of spy operations. They don't always have clean story lines that are executed with the suave expertise of James Bond. I find it ironic that Ian Fleming was actually a member of British Naval Intelligence at the time and contributed his prolific imagination to the planning of Mincemeat. Macintyre explains how Fleming read a mystery novel that began with a dead man carrying a set of documents that turn out to be forged. He incorporated the idea into the Trout Memo, a series of proposals for deceiving the Germans.British Naval Intelligence liked the idea and Macintyre unfolds the blunders, gaps, and trial-and-error approach that comes with every intelligence operation, no matter how well planned. Macintyre writes, "Operation Mincemeat began as fiction, a plot twist in a long-forgotten novel, and approved by yet another novelist."Operation Mincemeat is the aptly named caper about a half-decomposed corpse that washed up on the shores of Spain in 1943 with a briefcase containing secret intelligence that American and British forces planned to attack Sardinia and German-held Greece. The briefcase contained a letter that spells out secret plans that American and British forces planned to cross the Mediterranean and launch an attack on German-held Greece and Sardinia. Hitler transferred a panzer division to the region and issued a statement that measures to protect Sardinia take priority over any others.Too late the Germans learned that the dead body was that of a vagrant who died of rat poisoning and that the new British uniform he was wearing had been "broken in" by a British Intelligence officer who was the same size. Since underwear was rationed during wartime, the corpse was dressed in the underwear of another dead man. To keep the body fresh, he was frozen until time for his journey.Macintyre spares no details on the problems of dressing a frozen corpse--his feet had to be thawed so the ankles would be bend. "I've got it," said the Coroner. "We'll get an electric fire and thaw out the feet only. As soon as the boots are on we'll pop him back in the refrigerator again and refreeze him." Macintyre then describes his transport in an insulated capsule that had been invited by Charles Fraser-Smith, who is believed to be the model for Q in Ian Fleming's James Bond novels.Operation Mincemeat was a success and the Germans took the bait hook, line, and sinker. When a hundred and sixty thousand Allied troops invaded Sicily--instead of Sardinia--on July 10, 1943, it became clear that the Germans had fallen victim to one of the more spectacular ruses of modern military history.

M**H

You will not be able to put it down!

Being a fan of everything to do with World War Two and studying History in school this book obviously appealed to me for many reasons! I love reading about stories throughout the war and stories about deception truly captivate me. I am very glad I picked this book and dove right in!!This story is not an untold story, it is about the transformation of an "unknown" corpse into the fictitious Captain William Martin, whose body turns into a body with a reinvented past life (love letters, hobbies and theatre life) then becomes the carrier of misleading information on the forthcoming invasion of Sicily, was deployed, apparently drowned, into the sea off Spain in 1943 as a "Trojan horse" to find its way back to German intelligence. In this story, the body of the homeless Welsh vagrant, Glyndwr Michael, proved so much more worthwhile in death rather than in life. This part of the story alone is fascinating but further more the book is about strange men, and the strange world they inhabited, behind the planning. In this world there was rivalry and ego which was found in abundance in Whitehall in those days. It is safe to say their egos may have got the better of them if it was not for the shared common enemy.You need to get this book for yourself to understand just how great it is, you will not be able to put it down.Please click on the “Yes” button below if this review has been helpful thank you

C**L

Hitherto unknown detail on a well known story

I was quite young when I read a serialised version of Ewan Montagu's "The Man who Never Was" in my Uncle's Reader's Digest! At some point I saw the film and so when the TV programme featuring Ben Macintyre came on a few years back (after he'd published the book) I rather sniffily commented that what more was there to know? Wrong - Ben Macintyre has a journalist's knack of getting interviews with people who really matter and writing in an entertaining, but accurate manner. I so enjoyed his book on Philby that I decided to revisit this wonderful piece of WWII deception. I remember (again as a child) talking to my father about it and him saying it was one of the finest pieces of deception carried out during the war.And what a marvellously motley crew of eccentrics they were - like Macintyre I was particularly fascinated by the ungainly but self effacing Charles Cholmondeley, who initially came up with the deception. The fearsome Admiral Godfrey ("M" in the Bond books), Ian Fleming himself flitting through the pages, the splendidly fearless Alan Hillgarth, the attache in Madrid, and last but not least Ewan Montagu himself. I'd forgotten that after the war he became Judge Advocate General of the Fleet. I joined as a Wren Stenographer, recording Courts Martial & Boards of Enquiry, and no President of a Board, or Naval Judge Advocate, ever wanted to invite interest in his proceedings by the dreaded Judge Montagu.Eccentric (some may say difficult, or just plain bonkers) people often rise to the surface during war - their skills which would be hard to match with peacetime mores find an outlet. Despite his race against time interviewing as many of the original team's survivors or their relatives as he could, Macintyre never satisfactorily concluded whether or not Ivor Montagu betrayed not only his country but his own brother. I felt Macintyre was more than generous to this man. Given that out of all of the protagonists, Ewan Montagu was the keenest to let people know how involved he was it does not seem unreasonable that he may have dropped hints to his brother (his letters to his wife certainly seem to bend the rules requiring the strictest security). Generally this was a generation who really took their wartime vows of secrecy seriously and many refused to discuss what they had done right up to their deaths (Cholmondeley, Hillgarth). Montagu on the other hand, seemed to revel in his fame once he had written the book, and pestered for recognition of the success of the deception right up to his own death. The repulsive Philby slithers through the pages occasionally, moaning about the costs in Madrid (was there nothing he would stop at to betray his fellow countrymen?)Then there's the fascinating cast of spies in the Iberian peninsula, their German counterparts and the various Spanish Naval personnel who nearly caused the whole operation to stall. Really, you couldn't make them up. I enjoyed this book immensely, and the due recognition given by Macintyre to the actual corpse - a Welsh derelict who committed suicide - was an honourable addition to this astonishing piece of deception.

J**R

gripping true story that reads like a thriller

This is the gripping true story of the Second World War deception operation by which the Allies managed to convince the Germans that the planned invasion of Sicily in 1943 was in fact a decoy and that the real invasion was to be targeted at Greece in the eastern Mediterranean and Sardinia in the western Mediterranean. The success of the operation paved the way towards the invasion of Italy, toppling Mussolini and taking that country out of the war, the first major breach in the Axis coalition. The whole story reads like a rather unlikely thriller, disguising a dead body in a Marines uniform, planting a carefully constructed series of fake documents on him, drafted and presented in such a way that they would convince the enemy of their genuineness. The key was "not merely to conceal what you are doing, but to persuade the other side that what you are doing is the reverse of what you are actually doing." To do this they had to create a whole backstory for the fictional dead Marines officer, Major William Martin, and concoct supporting evidence for the documents and other materials found in his possession that would withstand investigation by any German or other enemy agent in Britain.The effectiveness of the plan also relied on understanding the psychology of individuals and nations, not just of the Germans, but also of the officially neutral Spaniards, juggling between those who were really pro-Axis and those (such as the Spanish navy) who were often pro-Allies. A lot of its success also depended on wishful thinking by those in the chain, wanting to believe the information, or wanting to ingratiate themselves by submitting the prized and explosive information further up the chain. It even convinced Hitler, supporting his entrenched belief that the Balkans was the soft underbelly of the Nazi Empire (ironically, Goebbels was the only leading Nazi who didn't fall for the deception).We meet a rich and varied cast of characters from all the participating nations, including on the British side a wide variety of people who were also novelists, most famously Ian Fleming, who took the original idea for the misleading corpse from a minor novel by a former top policeman published in 1937. (That said, this connection may not be so surprising as "the greatest writers of spy fiction have, in almost every case, worked in intelligence before turning to writing [.] Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, John le Carré.") We also come across the crucial role played by non-existent agents to deceive the other side and draw attention away from the activities of real agents - "Real agents tended to become truculent and demanding; they needed feeding, pampering, and paying. An imaginary agent, however, was infinitely pliable, and willing to do the bidding of his ....... handlers at once, and without question."One of the other tensions and fine balances the Allies needed to show once the body had been discovered was that of seeming to be reasonably alarmed when the papers were lost, but without making too serious an effort to recover them, and hoping that they would not be returned unopened by a friendly Spaniard. In the author's words, "in reality if top-secret plans really had fallen into enemy hands, and the breach of security was detected, then those plans might well be abandoned, or at least substantially altered. The Germans must be made to believe that they had gained access to the documents undetected; they should be made to assume that the British believed the Spaniards had returned the documents unopened, and unread. Operation Mincemeat would only work if the Germans could be fooled into believing that the British had been fooled." Such multiple levels of motivations go to make this such a fascinating and thrilling read - if a spy novel published today had this plot it might well be dismissed as too far-fetched to be believable.The leading instigators of the deception Ewen Montague and Charles Cholmondeley deserve great credit for their massive, but necessarily secret, contribution to ensuring the Allied victory on the European continent. After the war, the details of the deception were kept under wraps for years, partly to protect Anglo-Spanish relations, though Montagu published a partial account in 1953, and a film version was released in 1956 in which, bizarrely, Montagu played the minor role of a senior military officer, while his own role was played by an American actor. The final mystery of the real identity of the dead body - a poor and luckless Welshman, Gwyndyr Michael, who probably committed suicide through ingesting - was not revealed until the 1990s, when an inscription was added to the Spanish grave of Major William Martin, the most fictional person to make a major contribution to winning a war.

A**R

Montagu’s book is far more readable

I was looking forward to reading this book having read The Man Who Never Was as a schoolboy over 60 years ago. Montagu’s book drives the narrative forward like a Bond novel. By contrast, this book plods along, overwhelming what is a cracking yarn with endless diversions to fill in every detail. Undoubtedly a more accurate and complete telling of the story but it never gripped me with the desire to press on and finish the book. By contrast I re-read The Man Who Never Was recently and finished it in a day. Exhaustive but exhausting.

B**7

Ben Macintyre never lets me down

Ben Macintyre never lets me down and I picked Operation Mincemeat when it was a Kindle 99p deal. This is the story of the wartime deception operation better known as The Man Who Never Was, due to the famous book and film of that name. I followed this by re-reading Duff Cooper’s novella Operation Heartbreak, published in 1950. I learned from Macintyre that Cooper’s book was the first public revelation that a dead body, carrying fake documents intended to fool the Germans as to where the invasion of southern Europe would take place, was dropped off the Spanish coast to be discovered. There was a possibility of Cooper being prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act but he said that if charged, he would say that he got the information direct from Churchill. His book is nothing like the truth. Most of the story is about an invented dim but honourable professional soldier, whose body was eventually used. The Man Who Never Was was the work of Ewen Montagu, one of the originators of the plan and was more accurate. Plenty of people objected to this, too but the book became a bestseller.

Trustpilot

2 months ago

1 month ago