Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Full description not available

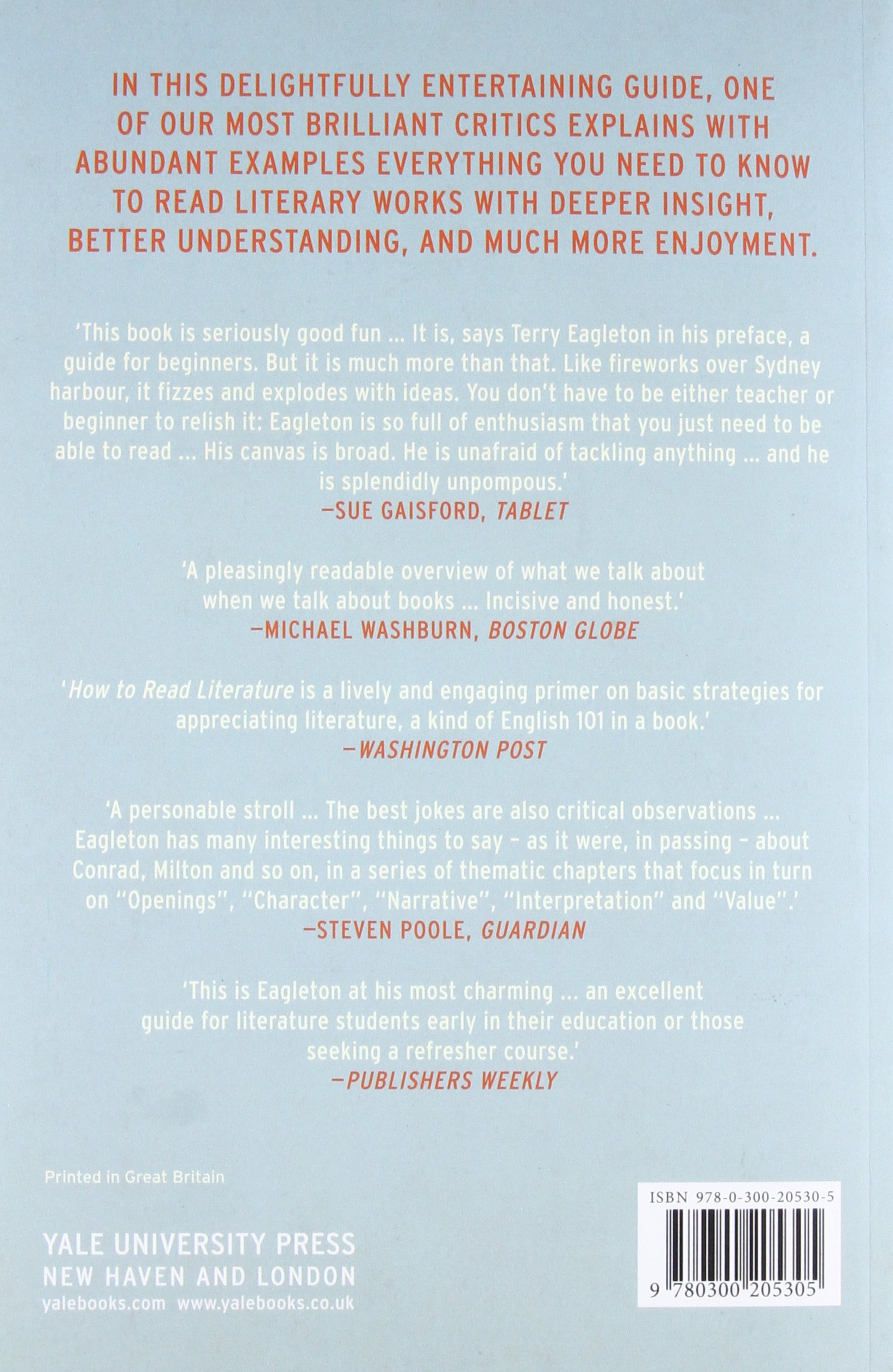

A**R

Close Reading Valued

Reading this, with pleasure, as a former English Lit major. Was surprised to see close reading valued, as I associated author only with postmod stuff. Instructional, lighthearted, glad I found it.

N**L

Eagleton is Still at It, Mostly for the Better

The institutional economist John Kenneth Galbraith once made the succinct and witty judgment that writing a book is inevitably an exercise in ego. Given that he was a prolific author and a celebrity intellectual, I imagine he was speaking for himself. Galbraith, however, wrote far fewer books than Terry Eagleton, and no doubt there will be more to come before Eagleton turns off his word processor and calls it a career. Evidently, Eagleton remains convinced that he has a lot more to teach us about a lot of things, especially language, literature, and culture and their nature and uses. I've never been disappointed in anything I've read by Eagleton, though The Idea of Culture seemed unduly cerebral and better suited to an audience that took itself more seriously than the readers of his other books, myself included.I expected How to Read Literature to have a lot in common with his earlier book Literary Theory. Evidently, however, literary theory and literary appreciation or, if you prefer, literary criticism, have less in common than I had imagined. Literary Theory, apparently, has more to do with the nature of language, and literary criticism emphasizes aesthetic criteria that govern how language is used in producing novels, short stories, poems, and other fictional forms. Theory and criticism, nevertheless, certainly have a substantial conceptual overlap.How to Read Literature, thus, may generate minor but annoying confusion as to the very nature of literature as a distinct creative activity. For example, in Literary Theory Eagleton made much of the once prevailing admonition that "a poem should not mean but be." Since poems are constructed of words, and words take their meaning from their relationships with other words, and words are the building blocks of language and literature, the distinction between literary theory and literary criticism becomes even harder to make with confidence. However, if an author such as Eagleton chooses, in a particular instance, to emphasize one over the other, it seems reasonable to overlook the artificiality of a hard and fast break between the two, at least for the time being.How to Read Literature is, for the most part, readily accessible, and it's not unduly difficult to follow Eagleton's discussions of openings, character development, the variable nature of narratives, and other pertinent topics. Nevertheless, Eagleton does not pander to the reader by choosing only easy examples with which to make his presentation. If anything, he shows off just a bit, displaying his impressive erudition and demonstrating the depth and complexity of his thought, sometimes to the point of contrivance for just this purpose. In truth, Eagleton fairly often over-interprets literature of varied genres. This is the sort of complaint that is often heard from mystified Freshmen enrolled in their first course in English composition, but toward the end of the book Eagleton acknowledges that patterns of alliteration, clusters of sumptuous words, instances of well-timed understatement, and other happy locutions attributed to an author's brilliance are very often produced unself-consciously. This does not rob them of their literary value, but it does undercut the claim that they were intentionally invoked to produce admirable literature. This, I think, has the salutary effect of making the writing of fiction seem less like industrial engineering and more like art.Furthermore, one need not agree with every judgment that Eagleton offers. Sometimes he seems to be simply wrong. This is conspicuously true of his analysis of what the takes to be misguided uses of empathy in understanding and explaining characters. If I understand him, Eagleton claims that empathy has no place in the production of fiction. His reasoning has an odd and, I think, demonstrably false basis, namely that if one is empathizing -- putting yourself in the place of another person -- by becoming that person you deny yourself the opportunity to observe him or her and gather material for use in your writing.This claim, however, seems absurdly wrong. George Herbert Mead's masterful Mind, Self, and Society gives a conspicuous place to taking the role of the other, in other words to empathy, in the development of social and communicative competence. This is how we learn about each other and acquire the ability to interact,Much more recently, in Adam Begley's biography Updike, the biographer very effectively describes John Updike as always maintaining an essential detachment from himself, enabling him to observe and record what he did and felt just as he was doing it. Updike was adept at empathizing with himself and thereby accumulating raw material for his writing. This, according to Begley, was a primary reason why so much of what Updike wrote is autobiographical.Even the smartest and most learned among us occasionally make some pretty consequential blunders. In this instance, I think that Eagleton became entangled in an overwrought convolution of his own making and outsmarted himself. It's ironic, moreover, that Eagleton rejected empathy but endorsed the use of sympathy, thereby risking spilling over into sentimentality.This review is a lot more unfavorable than I wanted it to be. Eagleton's discussions of classical realism, romanticism, and modernism are very informative and useful. His failure to give more attention to post-modernism is consistent with choices he's made in some of his other books, such as After Theory. He pays tribute to post-modernism in the abstract, but seems averse to celebrating it concretely. In Why Marx Was Right he gives the distinct impression of being pretty much fed up with it. In fact, Eagleton goes so far as to judge modernism, not post-modernism, to be the most important development for literary and cultural studies in the 20th Century.Eagleton, whatever his errors in judgment and penchant for self-aggrandizement, alerts the reader to important aspects of literature that are often overlooked or discounted. He is indeed endorsing "slow reading," and to do that as insightfully as Eagleton must be exhausting, something that is mastered over time through repeated applications.No, Eagleton never comes right out and says "here is a list of the attributes of all fine literature," and he acknowledges that individual taste has a legitimate role in evaluating what we read and how much we enjoy it. More compelling, though, are his repeated acknowledgments that literary criticism unrelated to time and place is something that cannot be realized. That he puts so much emphasis on context, including social organization and relationships, as essential factors in evaluating literature is very much to his credit. Eagleton may be a bit of a showoff, but he's also an extraordinarily capable writer who rarely lets his ego render his work inaccessible to unspecialized readers.

D**L

The best book of its kind

I think this is the best of the books of its kind and is accessible to beginners but still valuable to experienced readers. By coincidence, I read English at Oxford and almost had Eagleton as a tutor; I'm sorry I missed that opportunity but feel I'm making up for a bit of the loss now. Meanwhile, I'm reading the book with a student who's talented in science but is currently struggling in literature: I hope it will help him see what to do when he reads fiction or poetry. (I've also looked at Thomas Foster's book, which I don't find to be as well balanced or comprehensive.)

H**R

Fantastic introduction to serious lit crit

This book is a totally captivating read, as well as the best (and by far the most painless) introduction to literary criticism and theory that I have seen. Eagleton keeps the lit crit jargon to an absolute minimum. He simply shows how to read well. But, of course, all of his vast knowledge of literary theory informs how he reads. That's what makes this book so valuable. You can actually see how a truly great literary theorist approaches works of literature.

E**N

and how wonderful he is for being so smart

Despite the title, it's not really a "How-to" book. It's just a list of all the things he's read, and how wonderful he is for being so smart. I think the whole thing is kind of smarmy and self-congratulatory. Evidently I'm WRONG - as my prof and all the English majors I know think this guy's amazing - but as a person who is not into literary criticism, I was hoping this would sort of make it easy for me and explain what to do step by step.As a book lover, I argue every point he makes in the book - I think you should love your books, I think you should love your characters. I think they are like special friends who never age and never go away, and yet you learn more about them each time you read a book over again. If you too love books, this book will make you sad. :(

A**.

Exactly as described and like new!

The book came earlier than I expected and it is exactly as described. I an very happy with my purchase and will buy more often from this bookstore! Thank you!

W**N

Great Read

What a romp! What fun! What wit! Thoroughly refreshed by it. Unexpected associations, and a rather droll account of bad writing at the ending!

L**R

Splendid, lucid...Eagleton!

Terry Eagleton, wears his erudition lightly in rendering accessibie the historical and formal complexity of a wealth of life-giving literary working works. Have fun: buy it!

Trustpilot

2 months ago

4 days ago